Research Update

Summary

IHP released its final pre-election Presidential Election voting intent update on 18 September, three days prior to the 2024 Presidential Election. This final update was not based on the SLOTS MRP model that had been used in previous estimates, but on an improvised model prepared in haste following detection of a large social desirability effect leading to substantial over-reporting of past voting for AKD. This over-reporting led the original IHP model to increasingly underestimate AKD support.

The final released estimates for the major candidates correctly identified the winner, but they had an average error of 4.1%. This might be considered respectable for a first effort, but performance fell short of IHP expectations.

The primary reason for the underperformance was the practical difficulty in finding a rapid solution to the problem of a rapid increase in social desirability bias in survey responses during the previous three months. This report reports the accuracy of the final estimates, discusses issues that arose in the last few weeks of survey tracking, undertakes further analysis of alternative solutions, and develops methodological improvements. The analysis suggests that using modelled estimates of individual level past voting choice instead of self-reported past voting choice would have circumvented the issue of social desirability bias and produced estimates with a more satisfactory level of prediction error. This result may have wider relevance to the general research on modelling vote intent in conditions of significant reporting bias.

How well did we do?

Short answer: Not so badly in the circumstances, but not as well as we would have liked.

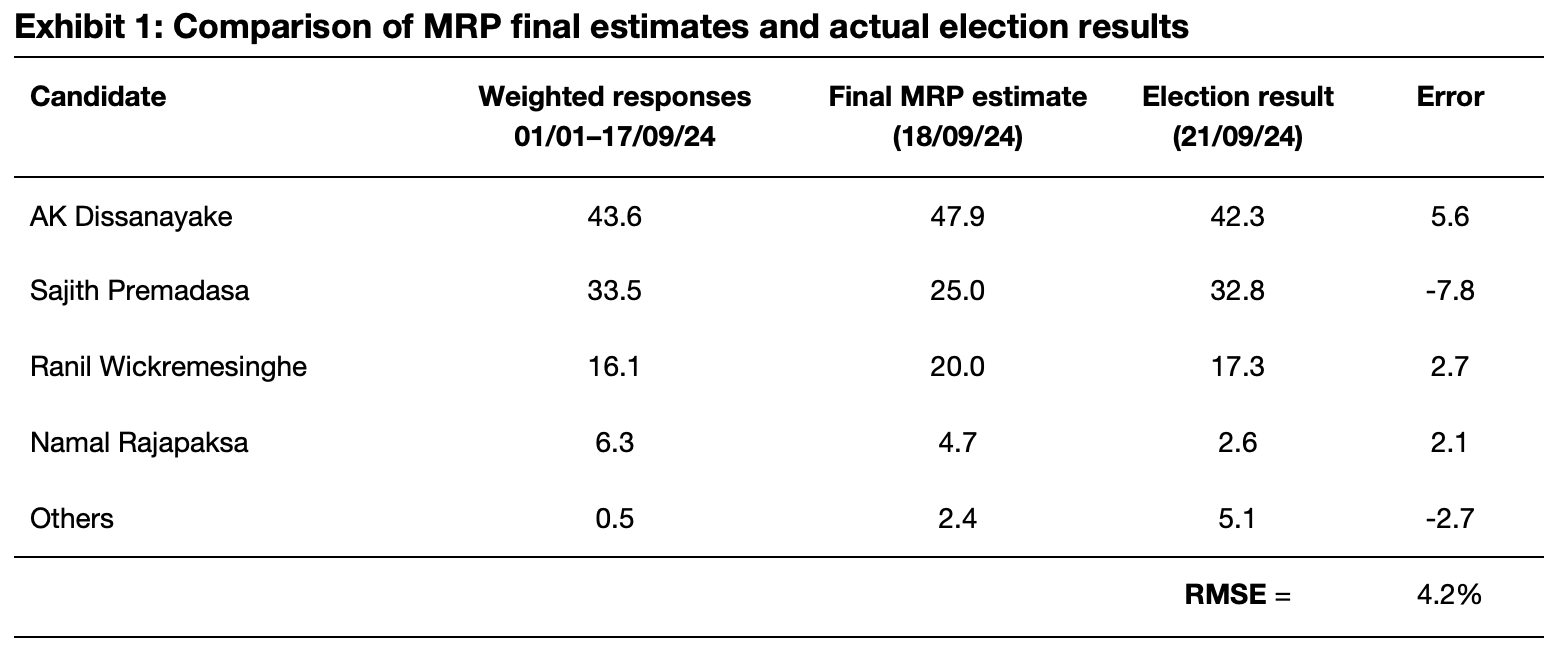

Our tracking of voting intent correctly identified the winner–AK Dissanayake–and that he would fail to win on the first count. Our internal estimates indicated also that he would win on a count of second preferences, with most people not casting a second preference and those that did breaking 2:1 in favour or Sajith Premadasa. We also correctly placed the three other major party candidates (Exhibit 1).

We overestimated AK Dissanayake’s {AKD} vote by 6%, and underestimated Sajith Premadasa’s by 8%. The Root Mean Squared Estimate (RMSE), a standard measure of polling accuracy that averages the errors, was 4.1%. This is almost double that in US state level Presidential Election polls, which are the most comparable, although polling a three or four-way race is harder than the two-way races that are the norm in the US.

Our previous tracking from 2023 through mid-2024 was notably closer to the actual result. The average difference between the average vote shares of candidates throughout 2024 and the final election result would have had a RMSE of just 2.3%. SLOTS data also showed for more than two years that the NPP was quite likely to win a Presidential Election.

I next discuss the discrepancy between our long-term tracking and the final estimates, and why we were forced to use an improvised model for the final estimates.

What went wrong in the IHP MRP model

IHP uses Multilevel Regression and Poststratification (MRP) to model voting intent based on responses to its daily SLOTS interviews. This differs from the usual methodology of typical public opinion sample surveys, which generate estimates by interviewing representative samples of the public. MRP remains relatively novel and has been used widely to date only in the UK. The method involves using survey data to statistically model the relationship between voter demographics and vote choice, and then using these statistical model estimates to project voting intent in a separate data file that is designed to represent the demographics and other characteristics of the overall electorate.

IHP chose MRP to overcome the challenge of tracking vote intent using relatively small monthly samples, which have averaged just 500–600 in the case of SLOTs. MRP conventionally has been used to estimate vote choice in small spatial units such as British parliamentary constituencies, where typical national surveys typically lack adequate sample size to provide reliable estimates. In IHP’s case, we adapted it to estimate voting intent in small temporal units, i.e., months or days. This adaptation of MRP to estimate differences in vote intent over time as opposed to over spatial units is relatively novel, although the underlying theory is the same.

A key variable used in IHP’s MRP model through August 2024 was past voting history. The SLOTS survey asked all respondents how they voted in the 2019 and 2020 national elections. Globally, how people voted in previous elections is one of the best predictors of current vote intent, and this is also true in the Sri Lankan data. In doing this, a problem that IHP faced was that a significant number of SLOTS respondents (33%) did not provide their past voting history, and those who refused to answer differed substantially from those who did. To overcome this, their past voting history was imputed through a statistical process called multiple imputation, which generates multiple estimates of past vote choice that reflect the uncertainty in any imputations. This imputed past voting history was then used in combination with other variables, such as age, gender, and income level, to model vote intent.

To our knowledge, this imputation of past voting history has not been used in other MRP analyses, and the problem of imputing past voting history remains a topic of ongoing research in the academic literature, so our approach could be considered novel. To implement it, we adapted a method from the epidemiological literature, which has been used to estimate national disease prevalence in a scenario where detection of the disease requires a test, and where there are non-random differences between individuals who do or do not participate in the test. This corresponded to the SLOTS context, where those refusing to divulge past voting history were different to those who did, with Gotabaya Rajapaksa voters much more likely to disclose this than other voters during 2021–2023. As implemented, our method assumed there was differential reporting by supporters of different candidates, but that this was due largely to differences in willingness to respond and not differences in truthfulness if they did respond. This assumption was supported by various data analyses through 2023.

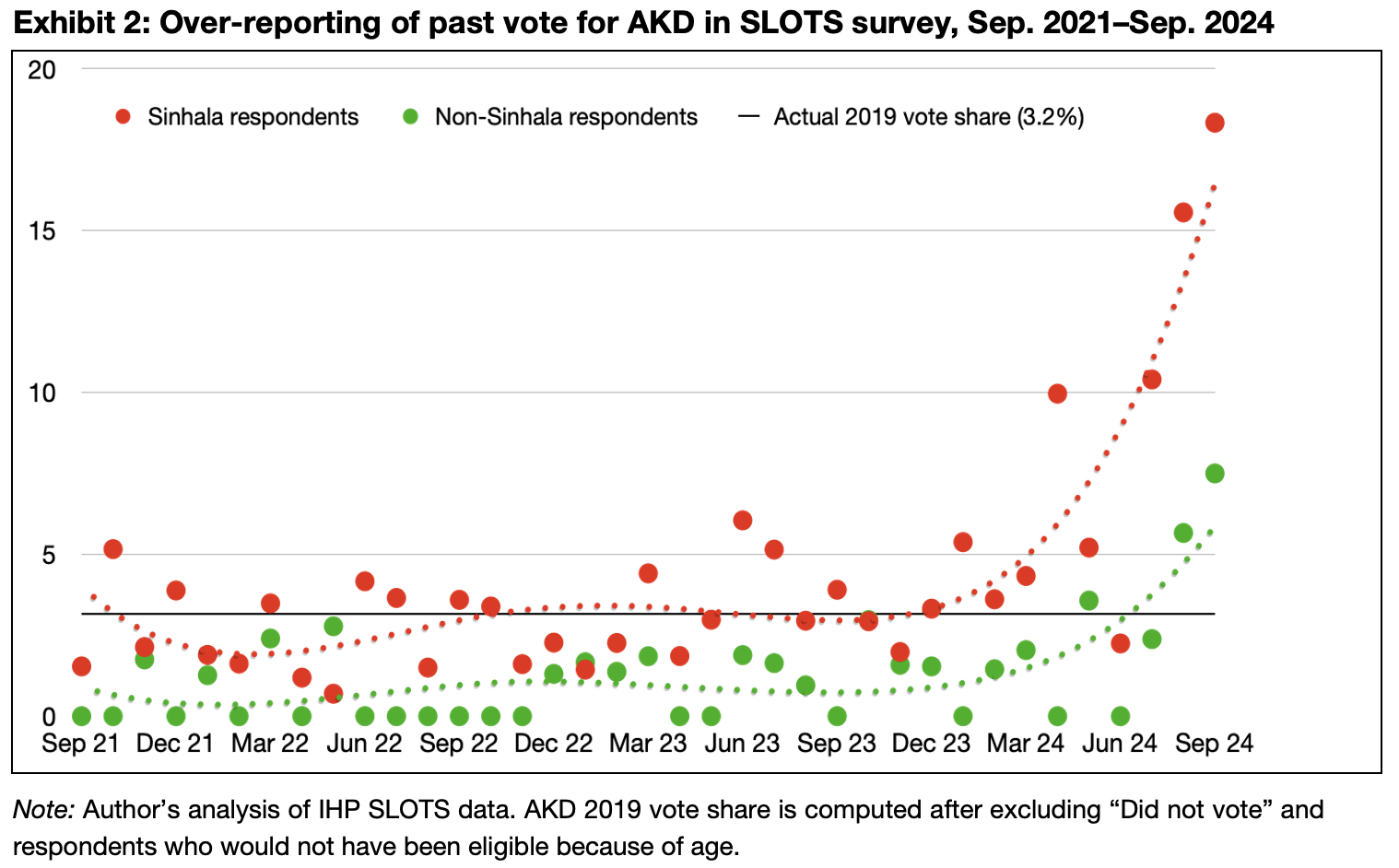

This assumption failed just prior to the election, when the percentage of respondents responding that that they had voted for AKD in 2019 increased from 2% (of all responses including refusals) during Jan. 2023–Jun. 2024 to 5%, 8% and 9% during the months of July to September 2024. As only 2.6% of the electorate voted for AKD in 2019, the immediate impact of this in the model was that these respondents, almost all of whom responded that their current vote intent was for AKD, were weighted down in the final estimates. This led the model to increasingly underestimate the AKD vote.

This change in responses was most likely due to social desirability bias. This involves respondents giving responses that they believe are socially desirable or will satisfy interviewers expectations. Although the IHP MRP model was designed to cope with some degree of social desirability bias, this extreme level of bias was outside its design parameters. Nevertheless, the emergence of this social desirability bias from early 2024 suggests that respondents were becoming more aware of overall public support for AKD (Exhibit 2).

Unfortunately, we did not detect this issue until one week before the election when the MRP model produced estimates that were in complete variance with the underlying raw data. Having identified the problem, we faced two choices. One was to not publish our final estimates, since we knew they were erroneous and flawed. The other was to not publish the flawed estimates, and to revise the model to mitigate the problem, and to communicate that we had changed the model. Neither option was a pleasant one. We decided in the interests of transparency to pursue the second option, but under significant time pressures owing to the Election Commission’s embargo on media reporting that was to start from 19 September.

The temporary fix that was implemented was to treat the change in reporting as a real social phenomenon, and to model it before using it as input into the existing MRP model. This revised model was used to publish our final estimates on 18 September, with a disclosure that we had changed the model.

This fix did improve the accuracy of the final estimates in comparison to the flawed output from the established model, so it represented an improvement. However, the overall accuracy was not satisfactory, even if it was the best that could have been done in the circumstances.

Conclusions

This analysis indicates that using individually modelled past voting choice instead of self-reported past vote choice would have provided a satisfactory solution to the problem of social desirability bias as encountered by the SLOTS survey prior to the 2024 Presidential Election. Indeed, its estimates would have been associated with far smaller errors than the original IHP MRP model and the September 2024 model revision, with an RMSE of about 1.8 (range of 1.2–3.5 depending on the specific parameters used).

This result confirms that the MRP approach is a feasible approach to track vote intent in the Sri Lankan context, and to do so with relatively small monthly samples (N=400–700) contacted by telephone and with high levels of non-response and reporting bias. It also confirms that it is possible to accurately track voting intent in Sri Lanka using well-designed surveys. The estimates generated by the final selected method (Model C using cubic splines with 8 knots) track closely the previously published IHP vote intent estimates until about May 2024.

The analysis presented here also suggests a novel approach to tackling the general problem of handling reporting bias in past vote choice. It confirms some recent work that found that using area level voting aggregates does not offer significant improvements, and points to the potential of using modelled individual level vote choice.